Ever Wonder HOW you Fuel up a FRAM DESTROYER, while under

way? This article should answer some questions.

DOG ZEBRA by

Dave Hood, GMT2

USS McKean (DD 784)

There’s great duty and there’s lousy duty.

There’s gravy assignments and there are *&%$ details.

Being assigned to the U.S.S. McKEAN DD784 in the late 70’s was a gravy

assignment. Our home port was in

Seattle at a leased municipal pier that we shared with two minesweepers, the

CONQUEST and the ESTEEM, and another FRAM, the USS HIGBEE DD 806. The nearest naval stations were either the Naval Shipyard

across Puget Sound at Bremerton or the Naval Support Activity at Sandpoint at

the other end of Seattle. There

were no signs saying, “Sailors and dogs keep off the grass.” The locals

actually liked us. As far as my

shipmates were concerned, the worst *&%$-sucking duty in the world would be

aboard a showboat cruiser like the U.S.S. LONG BEACH in a place like San Diego,

or, even worse, anywhere on the east

coast.

There’s great duty and there’s lousy duty.

There’s gravy assignments and there are *&%$ details.

Being assigned to the U.S.S. McKEAN DD784 in the late 70’s was a gravy

assignment. Our home port was in

Seattle at a leased municipal pier that we shared with two minesweepers, the

CONQUEST and the ESTEEM, and another FRAM, the USS HIGBEE DD 806. The nearest naval stations were either the Naval Shipyard

across Puget Sound at Bremerton or the Naval Support Activity at Sandpoint at

the other end of Seattle. There

were no signs saying, “Sailors and dogs keep off the grass.” The locals

actually liked us. As far as my

shipmates were concerned, the worst *&%$-sucking duty in the world would be

aboard a showboat cruiser like the U.S.S. LONG BEACH in a place like San Diego,

or, even worse, anywhere on the east

coast.

For an ASROC Gunners’ Mate, a gravy underway watch

station was either sonar, after-steering or the ASROC control station.

A lousy watch-station was anything the Bos’n Mates had to man, such as

forward lookout, aft lookout and any bridge watch.

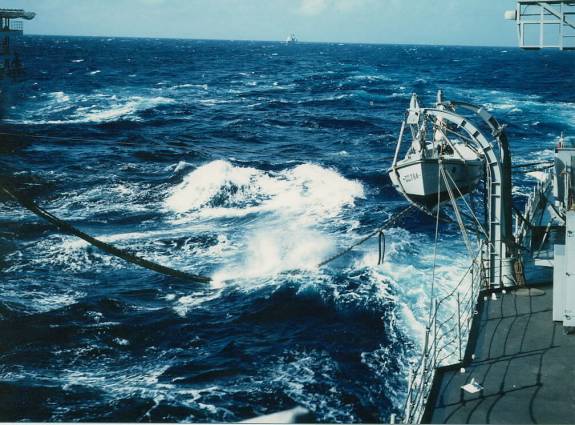

During an underway replenishment (UNREP) a horrible

assignment was line handler. A

gravy assignment was ship-to-ship phone talker.

Line handlers were on the main deck, some six feet above the waterline,

were always wet and cold, no matter how calm the seas were.

The ship-to-ship phone talker stood on the flight deck on the O-1 level,

got to see everything, stayed dry and got the opportunity to shoot the breeze

with his counterpart on the other ship.

If you’re a destroyer sailor, you’re familiar

with an UNREP. If you’re not a

Tin Can Sailor, let me explain the process.

Ships at sea burn a lot of fuel. (I heard that the typical fuel

consumption was 100 gallons per HOUR.) Destroyers

may get their best fuel economy at, say 15 knots.

At that speed, a FRAM has a range of 5,800 miles.

But remember - this is a destroyer story, written by a destroyer sailor

to be read by other destroyer sailors who have all served aboard destroyers.

And what is it that destroyers like to do best? We like to go real fast.

And the only thing that consumes more fuel then a destroyer with all of

its boilers lit off is the space shuttle on take-off.

About every three days we would need

to top off. The “Heavy”

could be a fleet oiler such as the USNS CAYUGA, a replenishment ship such as the USS MOUNT SHASTA or

even an aircraft carrier. The

“escort” would pull up alongside the “heavy” at about 15 to 20 knots and

try to maintain a constant distance of about 120 feet apart.

A shot-line would be fired from one ship to the other.

Attached to the projectile was a spool of common “550” parachute

cord, orange in color. The

“heavy” would attach a heavier line to their end of the shot-line .

The escorts line-handles would haul the shot-line back aboard.

Then the heavier line would be pulled aboard.

To the heavier line, the “heavy” would attach an even heavier line.

Spliced onto that line would also be the sound-powered phone line. The

phone-talker (me) would plug in and be able to speak directly to his counterpart

on the other ship. That heavier

line would be pulled aboard by the line-handlers.

Finally, the “heavy” would attach a steel cable to the end of the

line and that would be pulled aboard the “escort’’.

The cable would be attached to a fitting on the “escorts” fueling

station. (On a FRAM, we

traditionally used the fueling station on the flight deck at the rear of the

ship-located forward of the rear 5” gun mount.

There was another fueling station forward, up on the torpedo deck-just

forward of the bridge. For some unknown reason, we rarely used this station at

sea.) The fuel probe would slide

down the cable and mate up with the fuel station.

The ships would then steam, side by side, for as long as it took to

transfer fuel. It usually took

about an hour. It always seemed to

take longer if the weather was crappy.

such as the USNS CAYUGA, a replenishment ship such as the USS MOUNT SHASTA or

even an aircraft carrier. The

“escort” would pull up alongside the “heavy” at about 15 to 20 knots and

try to maintain a constant distance of about 120 feet apart.

A shot-line would be fired from one ship to the other.

Attached to the projectile was a spool of common “550” parachute

cord, orange in color. The

“heavy” would attach a heavier line to their end of the shot-line .

The escorts line-handles would haul the shot-line back aboard.

Then the heavier line would be pulled aboard.

To the heavier line, the “heavy” would attach an even heavier line.

Spliced onto that line would also be the sound-powered phone line. The

phone-talker (me) would plug in and be able to speak directly to his counterpart

on the other ship. That heavier

line would be pulled aboard by the line-handlers.

Finally, the “heavy” would attach a steel cable to the end of the

line and that would be pulled aboard the “escort’’.

The cable would be attached to a fitting on the “escorts” fueling

station. (On a FRAM, we

traditionally used the fueling station on the flight deck at the rear of the

ship-located forward of the rear 5” gun mount.

There was another fueling station forward, up on the torpedo deck-just

forward of the bridge. For some unknown reason, we rarely used this station at

sea.) The fuel probe would slide

down the cable and mate up with the fuel station.

The ships would then steam, side by side, for as long as it took to

transfer fuel. It usually took

about an hour. It always seemed to

take longer if the weather was crappy.

One night off the California coast we pulled up alongside

the aircraft carrier USS KITTY HAWK CV 62. As soon as our communications were

established I told my counterpart that we were requesting 40,000 gallons of DFM

and that the maximum pressure that we could receive was 100 psi.

“Wait one,” came the response.

“Kitty Hawk, McKean. The minimum pressure that we can send is 120psi.”

“Wait one.” It was my turn to use the standard Navy response phrase.

I told that to the engineering representative and he told me that it

shouldn’t be a problem.

“Kitty hawk, McKean. We are standing by to receive 40,000 gallons of DFM

at 120 psi MINIMUM.”

“Roger that McKean. 40,000 at 120 minimum.”

Did you notice that I started the preceding paragraph by

saying, “One night?” That’s

right. Night. As in dark. Real dark. Middle

of the freakin’ ocean dark. One

thing about US Navy warships at sea at night: they don’t like to show lights.

Pure darkness is the rule. The

only topside illumination comes from special floodlights that have red lenses.

They project just enough light for you to see what your doing but not

much more then that. Did you notice that I started the preceding paragraph by

saying, “One night?” That’s

right. Night. As in dark. Real dark. Middle

of the freakin’ ocean dark. One

thing about US Navy warships at sea at night: they don’t like to show lights.

Pure darkness is the rule. The

only topside illumination comes from special floodlights that have red lenses.

They project just enough light for you to see what your doing but not

much more then that.

So there we were. It

was the middle of the night in the middle of the ocean.

Two ships tethered together steaming at 22 knots.

My ship weighed 2,250 tons, the other weighed 86,000 tons.

We were 390’ long and 40’ wide.

The KITTY HAWK was 1,069’ long and 252’ wide. Our main deck was 6’

above the waterline. The KITTY

HAWK’s flight deck was 85’ above the waterline. They had the gas and we

needed it. Everything was equitable.

After awhile the Engineering rep told me to tell the Kitty Hawk that our

tanks were nearly full and for them to prepare to cease pumping.

“McKean, Kitty Hawk. Standby to cease pumping.”

“Kitty Hawk aye. Standing by.”

Five minutes later and I was instructed to pass on the word to cease

pumping. I was instructed that we

would then want a “Back Suction and then a Blow Down.”

(The ship-to-ship fueling hose is corrugated rubber and about 5” in

diameter and several hundred

feet long. It must hold hundreds of gallons of fuel.

A “Back Suction” is supposed to suck the fuel out of the hose and

back in to the tanker’s fuel tanks. A

“Blow down” is the forcing of compressed air through the hose to blow any

vapors into the receiving ship’s fuel tanks.)

”McKean, Kitty Hawk. Standby for your back suction and blow down.”

“McKean aye. Standing by.”

There are no instruments nor are there any gauges on the

flight deck. Nothing to indicate

what is happening. But I could tell

something wasn’t right. Instead

of the sucking, wheezing sound of fuel being sucked OUT of the fuel hose, I

heard something different, something unfamiliar.

Before I could figure out what was different I heard the new sound of

popping metal and expanding gasses. I

could now no longer see the fuel probe. It

was swallowed up in a fog. The fog

then expanded forward towards me. That didn’t make any sense.

We were moving forward at 22 knots and yet the fog was coming up from

behind and catching up with us. And

then the fog swallowed up me. It was wet and it smelled. It clung to me and

penetrated my clothing. It was

fuel! I realized what happened. Instead

of giving us a “back suction” and sucking out all of the remaining fuel in

the hose, the KITTY HAWK started off with a “blow down.” The remaining fuel

was trying to be forced into our already full tanks. The HP air driving the fuel was atomizing it and the fueling

station’s seals blew under the pressure.

The entire aft end of the ship was enveloped in an expanding cloud of

fuel!

I could feel the fuel penetrating my clothing and

clinging to my skin. “CEASE

PUMPING! CEASE PUMPING! CEASE PUMPING! McKean, Kitty Hawk! Stop your

goddamn pumping!” I again looked at this cloud of fuel that had swallowed

us up. I began to envision someone

coming out on deck: someone ignoring the fact that the smoking lamp was off. I

looked at the fuel fog that swallowed up the red lens flood lights. I wondered about the condition of the waterproof gaskets.

I just knew that at any moment the vapors would ignite. Would I be aware

of the flash? Would it instantly sear me? Would

I have time to see it ignite and then envelope me?

I took of my helmet and let it fall to the deck.

I reached behind my neck and undid the sound-powered phone set. I was

about to discard that too and then run. But

run where? I’m on a ship. In the

middle of the ocean. There was

nowhere to run to. It wouldn’t

where I ran to. If the ship

exploded I would be just as dead on the bow as I would on the flight deck.

And if I was to die I might as well die on my station doing my duty.

I put the phones and helmet back on.

By then the KITTY HAWK must have realized their error for they were now

giving us our back suction. By the

time that was done the wind blowing over the ship had dissipated the fuel fog.

The KITTY HAWK retracted the fuel probe and I disconnected the phone set

and tossed their phone line over the side. I don’t recall if I sealed the jack

in a plastic bag or not. We

released the pelican hook and let the cable go.

We maneuvered to starboard and got some distance between us and the KITTY

HAWK and then returned to our lifeguard station in her wake.

All of us on the aft station were hosed off with a 1 ½” fire hose and

then excused from water hours so we could take a hot fresh water shower.

Two days later we again refueled from the KITTY HAWK.

|