Note: There are a lot of acronyms in this story......they are all

discussed in detail at the end under "Definitions"!

THE OIL KING

By Richard H. King, CDR USNR-Ret.

At the time of this story, CDR King was LT JG, Main Propulsion

Assistant (1965-1968),

(Assistant Engineering Officer for Main Propulsion)

U.S.S. CHEVALIER (DD-805)

The FRAM destroyer was

essentially one of many versions of late WWII destroyers that were

"life extended" by virtue of a program called FRAM (Fleet Rehabilitation

and Modernization Program). Some of the FRAM'd Destroyers eventually ended

up with twenty five years service in our Navy and thirty more years in a smaller Navy (South Korea, Taiwan and South America, plus Greece and

Turkey). The FRAM program began in the late fifties and was ended in

the early sixties. The common thread, good and bad, was that these destroyers

were mechanically reliable.

years in a smaller Navy (South Korea, Taiwan and South America, plus Greece and

Turkey). The FRAM program began in the late fifties and was ended in

the early sixties. The common thread, good and bad, was that these destroyers

were mechanically reliable.

They were also labor

intensive; everything in the engineering plant was manually operated

including the water level of the steam drums in the boilers. It took about

20 engineers around the clock per watch to man one of these things as they

needed to operate at a steady 600 PSI. The 1200 "pounders" (lbs per sq. inch operating pressure) came later and had

some design problems. The main, turbo and auxiliary steam lines on a FRAM

Destroyer had bolted flanges which ship's repair force could repair or at least

do a "ship to shop and back" repair (by

removing the bad piece, carrying it to a shop, picking up the new piece a few

days later and re-installing) . The 1200 pounders had all welded

steam connections and only a highly certified welder could work on them

followed by extensive x-ray and similar tests requiring expensive test equipment

carried only by some tenders. That is why ship's force generally could not do

their own steam line repairs on Post FRAM Ships.

And although they were supposed to need less

engineers per watch than FRAM DESTROYERS, that goal was never achieved. They had the

same number of boiler technicians (BTs) on watch per boiler, except they became tired, bored and

sleepier quicker when the automated system was actually working and when the

"s" "h" "t" "f" they did not have the

options FRAM BT's had. And when there were problems, problems a FRAM

crew could fix with ship's force, only a shipyard could fix a 1200 pounder. So

what did we gain? Hardly nothing. Back to the drawing board. Hence

the gas turbine Spruance Class.

Enter the OIL KING !

The "Oil King" was the boiler

technician (BT) in charge of the some 200,000 gallons of black oil (NSFO) we carried in about twenty different tanks,

including four "ready service" tanks (two forward and two aft) and three amidships tanks that we

rarely tapped.

The OIL KING had watch stander's liberty both underway and in port and an open

gangway under most circumstances. According to some "BUPERS" (Bureau

of Personnel) manning document, on a FRAM it was supposed to be an E-7 position

during wartime, E-6 during peacetime. He had his own little shack with

laboratory equipment and had to test feed water quality and fuel oil quality on

a regular basis (several times a day on feed water). We had two fuel oil

transfer pumps which he or his assistant used every few hours to move oil around

from storage tanks to the service tanks to keep the ship on an even keel.

gallons of black oil (NSFO) we carried in about twenty different tanks,

including four "ready service" tanks (two forward and two aft) and three amidships tanks that we

rarely tapped.

The OIL KING had watch stander's liberty both underway and in port and an open

gangway under most circumstances. According to some "BUPERS" (Bureau

of Personnel) manning document, on a FRAM it was supposed to be an E-7 position

during wartime, E-6 during peacetime. He had his own little shack with

laboratory equipment and had to test feed water quality and fuel oil quality on

a regular basis (several times a day on feed water). We had two fuel oil

transfer pumps which he or his assistant used every few hours to move oil around

from storage tanks to the service tanks to keep the ship on an even keel.

I have a vivid picture in my mind of the Oil King sitting

at the Chief Engineer's Desk in the Chief Engineer's stateroom studying the tank

tables and charts (the

stateroom designated for the Chief Engineer was slightly to port of the after

service tanks and that was where their sounding tubes were located, or just

outside the door). Good thinking on the part of someone at BUPERS because

if an officer's stateroom had to be invaded day and night every few hours by

someone, it best be the Chief Engineer who best understood why. Either the Oil

king or his assistant would be in and out of there throughout the night taking

soundings with a flashlight.

When we refueled (whether at sea or in port) he took

command of a sound powered phone circuit that led to each of the twenty tanks.

With diagrams and papers in front of him, he would direct other

BT's when to shut key valves and eventually when to call for cease pumping.

It was LT Al Sherman's and BT2 Richard Morton's opinion that the best rank for

the job on a FRAM was a senior E-5. Chiefs were too lazy to do it right

and First Class were better used as being in charge of a fire room. But he

had to be the best and brightest BT2, smart as a whip and stable as a rock. Even

as early as the late sixties, an oil spill off Shelter Island Yacht Club in San

Diego Harbor could ruin a lot of officer's day including the Captain's.

The Oil King had direct access to

the Captain, Chief Engineer and of course the junior officer and Chief in the

chain of command. He would fill out a small form every morning

about our fuel state, with input from the Water King (a Machinist Mate) as to water volume

but which included the results of his laboratory tests as to water quality and

under our system he was supposed  to

route a copy to the Chief Engineer, MPA, Chief BTC and Chief MMC before lunch.

The original copy went to the Captain as part of the "noon report".

We were blessed with some good ones on "Chevy" during my watch,

but the best of the greatest was in my humble opinion, BT2

Nathaniel Thomas from Virginia. to

route a copy to the Chief Engineer, MPA, Chief BTC and Chief MMC before lunch.

The original copy went to the Captain as part of the "noon report".

We were blessed with some good ones on "Chevy" during my watch,

but the best of the greatest was in my humble opinion, BT2

Nathaniel Thomas from Virginia.

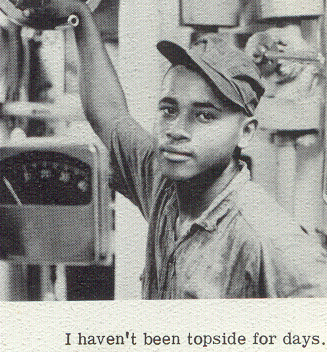

The picture at left was taken before he became "Oil

King", he was then "top watch" and maintenance chief in the

forward fireroom. At the time, he was the only Black (of any rank) in

"B" Division and was highly respected. He really caught my attention

when I realizes he was doing 90% of the paperwork for both firerooms (MDC/PMS).

We also had an interesting unannounced "FLAG

VISIT" in the forward fireroom when he was steaming a boiler, in charge.

I had twenty seconds to tell him (by phone) a four star was going to be climbing

down the ladder to his boiler flat. The Admiral challenged the

"perfection" we had down there and really grilled Petty Officer

Thomas. Thomas was great, he said "we work hard and long" but

once you build a near perfect plant, it is easy to keep it that way. WOW,

I was impressed, as was the four star Admiral. The

Admiral grilled Thomas, the Captain stood behind the Admiral and I stood

behind the Captain waiting for disaster to strike. Nathaniel Thomas argued

with the Admiral and won his case. I know the Admiral was impressed. If

I recall directly, the Admiral was Vice Chief of Naval Operations Admiral

Revero. I was shaking. Petty Officer Thomas remained calm and

collected. He stood his ground and defended his boiler flat

that he was in charge of.

Now for some definitions:

-

BTC stands for "Boiler Technician Chief"

(E-7) in olden days "Boiler Tender Chief".

-

MM stands for "Machinist Mate", the rate

that handled the steam turbines, turbo generators, evaporators, condensers,

etc.

-

In simplistic terms, the "BT's" made the steam and the

"MM's" put that steam to work and sent the condensate back to the

BT's to make more steam. It was called the

"steam cycle" because in theory you used the same water over and

over and over again.

-

"MPA" stood for "Main Propulsion

Assistant" which I describe to civilians (easier to understand) as

"Assistant Engineering Officer for Main Propulsion". Or on a

merchant steamship, "First Engineer" (after the Chief

Engineer).

-

"MMC" stood for "Machinist Mate

Chief (E-7). Actually, we (on the USS Chevalier) had a "SPCM" (E-9). "Steam Propulsion Chief Master".

Same as Sergeant Major in the Army or Marine Corps. The idea was that

upon moving from the rate of E-8 to E-9 you were suddenly an expert in both

of two closely related rates. And that was fairly much true, but it is

my understanding that we went back to the way things were in the olden days

and the rate of SPCM has been abolished.

"SPCM" (E-9). "Steam Propulsion Chief Master".

Same as Sergeant Major in the Army or Marine Corps. The idea was that

upon moving from the rate of E-8 to E-9 you were suddenly an expert in both

of two closely related rates. And that was fairly much true, but it is

my understanding that we went back to the way things were in the olden days

and the rate of SPCM has been abolished.

-

The E-9 rates are now MMCM (Master Chief

Machinist Mate - E-9) or BTCM (Master Chief Boilerman

- E-9).

-

MDC and PMS. In the days before you had a

computer, the Navy was trying to use mainframe computers to sort out a lot

of information concerning the maintenance of Naval ships.

"MDC" stood for "Maintenance Data Collection".

"PMS" stood for "Planned Maintenance

System". There were a bunch of forms, which were very

complicated, that sailors had to fill out, and everything was done in code. There

was a thick book that came with the system where you found your problem and

looked in the book and found the right code.

I remember one interesting case involving a

"chair". What, a chair? Yes, a chair, in the

engineering log room. It was an aluminum chair and the seat of the

chair was broke. We were under a moratorium for buying new office

furniture. I figured if the tender (a ship used to supply destroyer's

with parts and supplies) would cut me a piece of plywood to screw onto the

chair, perhaps with some padding and some sort of vinyl covering, I could

re-cycle that chair for another ten years.

So I tried to fill out a "4700-2C" form for the

tender carpentry shop to make me a new "seat" for a chair.

All I was asking was for the tender carpentry shop to cut a piece of

plywood, apply some padding and stretch some sort of naugahyde over it.

The problem that developed was that there was no "code

number" in the MDC system for a chair. I took that case as

a challenge and spent weeks at it. My chair was eventually fixed, but

the amount of paperwork it took outweighed the chair. The system

was not user friendly. For example, if a bearing wiped on a pump

shaft, the sailor who fixed it had to fill out a 4700-2B (repair completed).

If

something was broke, but we didn't have the needed part, he was supposed to

fill out a 4700-2D (repair deferred). If the ship wanted either a

shipyard, SRF or Tender to tackle the job, a 4700-2C was filled out. This

was an early attempt by the Navy to use computers to replace the memory of

the senior petty officers and officers actually on board as to what

was done to what machinery when and what we need do to soon. We

had no computers on board. But about six months after all these little

forms had been sent in, we would receive a fifty pound box of paper of

computer print out (perforated at the edges) telling us what we did and what

we needed. Nobody ever ploughed through those reams and reams of

material because by the time it got back to the ship, it was

ancient history and by that time we had new problems. Things may

have got better later, I will let our younger members address that. If

something was broke, but we didn't have the needed part, he was supposed to

fill out a 4700-2D (repair deferred). If the ship wanted either a

shipyard, SRF or Tender to tackle the job, a 4700-2C was filled out. This

was an early attempt by the Navy to use computers to replace the memory of

the senior petty officers and officers actually on board as to what

was done to what machinery when and what we need do to soon. We

had no computers on board. But about six months after all these little

forms had been sent in, we would receive a fifty pound box of paper of

computer print out (perforated at the edges) telling us what we did and what

we needed. Nobody ever ploughed through those reams and reams of

material because by the time it got back to the ship, it was

ancient history and by that time we had new problems. Things may

have got better later, I will let our younger members address that.

Comments on the Navy's "Planned Maintenance

System" (PMS)

I think it was

around the time our reserve crew was on McKean that I was introduced to PMS.

"What are we doing this weekend?" "Were doing PMS on the

condensate pumps". I still believe in the theory of if it ain't

broken don't fix it, but Oh No, we had to unbolt the deck plates on the lower

level and disassemble a perfectly good condensate pump while standing in

the bilges. The shaft and impeller were removed and micrometer readings

taken of the wearing rings and other dimensions. Then it had to be put

together again and you didn't just run down to Manny, Mo, & Jacks Condensate

pump supply house either for parts. All the gaskets had to be made by hand

using a ball peen hammer on the edges and a gasket cutter for the holes.

If we were lucky Engineering Supply had some bearings left over from WWII, but

most of the time nothing was wrong with the pump. Robert TeGroen

|