|

|

|

|

As seen at left, a QH-50C DASH approaches the Allen M.

Sumner class destroyer, USS HUGH PURVIS (DD-709), for landing. The

successful deployment of DASH on over 160 U.S. Naval Destroyers, Destroyer

Escorts, Tenders, Cruisers and a Battleship occurred due to the hard work

and dedication of.........

|

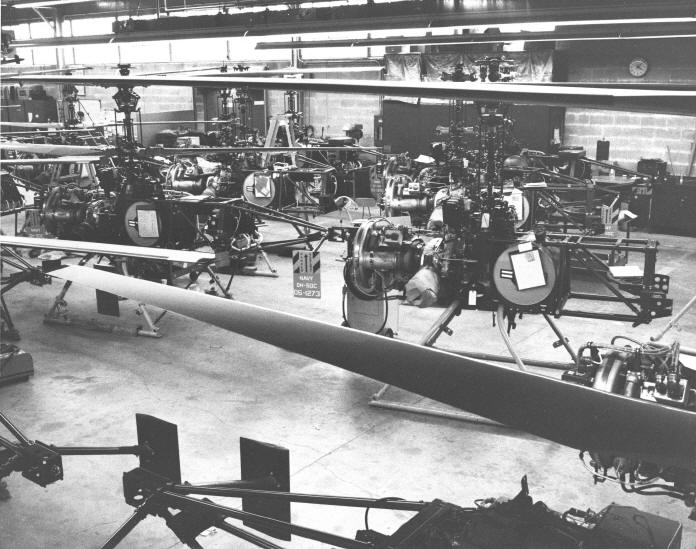

.......the Gyrodyne employees who worked at

Gyrodyne building the parts, assembling the drone helicopters, flight

testing the completed system, testing the finished FRAM work at the U.S.

Navy yards to serving on ship as Technical Representatives to insure the

system was operated correctly. THESE were some of the many job

descriptions required for the ONLY deployed and mass produced Vertical

Takeoff and Landing Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (VTOL UAV) program in the

history of modern warfare and Gyrodyne employees, such

as those seen at right in August 1969, made the DASH system

work. The Following is a sample of their Memories of working for

Gyrodyne.

|

|

|

I was so surprised and

delighted to view the "GYRODYNE' web site. I worked for Gyrodyne at

St. James L. I. as a draftsman from 1963 to 1966. If you've got a moment

here's a short story about my working days at Gyrodyne.

Back in the spring of

1963 1 was a laid-off Jr. Draftsman from Grumman Aircraft. We had just

finished working on a re-draw program for the A-6 Intruder (it was

designated A-2F at the time) and were about to perform a re-draw program

for the E-2A AWACS aircraft, (that was designated at the time W-2F). We

were all "job shopper' draftsman with perhaps a year or two

experience out of work on beautiful Long Island in the spring enjoying an

unexpected "spring break". I had a brand new convertible and had

a ball going to the beach with my buddies every day that we could. Well

after a few weeks of "spring break" my father took things into

his own hands.

My dad was a retired

N.Y.C. policeman who worked as a butcher after he retired at a fairly

young age. He worked for a supermarket called Blue Jays in St. James, L.

I. He waited on a man, Mr. Papadakos, who owned a helicopter company. My

dad would personally cut meat for Mr. Papadakos. My dad mentioned to Mr.

Papadakos that I was an unemployed draftsman and would you know it the

next day, a Saturday, I was interviewed by my future supervisor Mr. Frank Jelly. The interview

went great and after taking a "psychological profile" test, Mr.

Jelly told me I was normal (my wife disagrees) and offered me a position

as a Junior Draftsman at a starting pay of $68 a week. One week later I

was working on the board (drafting board that is) at Gyrodyne. I was 19

years old (got nicknamed "the kid") and was I thrilled to see

the parts and pieces that I drew on paper being manufactured and installed

on the QH-50C's and QH-50D's. I worked on everything from casting drawings

to machining drawings of the castings to sheet metal brackets to pipe

assemblies to functional checking fixtures.

was interviewed by my future supervisor Mr. Frank Jelly. The interview

went great and after taking a "psychological profile" test, Mr.

Jelly told me I was normal (my wife disagrees) and offered me a position

as a Junior Draftsman at a starting pay of $68 a week. One week later I

was working on the board (drafting board that is) at Gyrodyne. I was 19

years old (got nicknamed "the kid") and was I thrilled to see

the parts and pieces that I drew on paper being manufactured and installed

on the QH-50C's and QH-50D's. I worked on everything from casting drawings

to machining drawings of the castings to sheet metal brackets to pipe

assemblies to functional checking fixtures.

One particular

experimental project was the design and installation of a recovery system

that suspended a DASH below the surface of the water by means of a large

inflated balloon if by circumstance the DASH ditched in the ocean. The top

of the inflated balloon had a hook eye attached so a helicopter could

snare it and return the DASH to the ship. This system was tested at the

Brooklyn Navy Ship Yard. They actually dropped a OH-50C from a crane into

the water and the system deployed as designed. I remember the blade shop

and how the blades were laminated and balanced. It was high tech for that

time and possibly even today. I also recall that during the 1963-1966

period that I worked at Gyrodyne, Mr. Papadakos had a friend in charge of

engineering (named Alex Pappas). Also at the same time the Navy rep. was

Commander Shapperty, or simply called "Shep" by his friends. (My

future in-laws knew him). A real nice gentleman. Another thing I remember

was that the Navy decided they wanted to name the QH-50D, so they held a

contest at the plant hoping the people that designed and built the

QH-50’s would come up with a good name. I submitted the name

“Subliminator” but I don't know if any name was officially chosen.

(Some clown submitted "Chicken of the Sea").

My memories of

Gyrodyne are so vivid. I learned so much, I felt I was doing something

important for our nation. The people I worked with I admired for their

skills and inventiveness. Gyrodyne laid the foundation for my working

career.

When I left Gyrodyne in 1966 I had just gotten engaged and had received an

offer from Fairchild Republic for compensation so much higher than what I

was earning at Gyrodyne that I really had no choice. (I was earning $82/wk

at Gyrodyne vs. $120/wk Fairchild-Republic offered). The hardest thing was

telling my supervisor and friend Frank Jelly about my decision. Frank did

the best he could by getting me more money to stay, about $3 more a week,

but I had to reject it. On my last day of work at Gyrodyne, July 8, 1966,

my co-workers took me out after work for a one last drink. As I said I was

engaged and the date of July 8,1966, was my future father-law's birthday.

I was to be at his birthday party that evening at 8:00 pm. I was doing

fine at my going away party and explained why I had to leave early because

of the future father-in-law birthday thing. Well I'm out in the

parking lot getting in my car to leave and who shows up late but Frank

Jelly, my supervisor. I explain why I've got to go and he tells me he has

to buy me just one drink. OK, just one!

When I left Gyrodyne in 1966 I had just gotten engaged and had received an

offer from Fairchild Republic for compensation so much higher than what I

was earning at Gyrodyne that I really had no choice. (I was earning $82/wk

at Gyrodyne vs. $120/wk Fairchild-Republic offered). The hardest thing was

telling my supervisor and friend Frank Jelly about my decision. Frank did

the best he could by getting me more money to stay, about $3 more a week,

but I had to reject it. On my last day of work at Gyrodyne, July 8, 1966,

my co-workers took me out after work for a one last drink. As I said I was

engaged and the date of July 8,1966, was my future father-law's birthday.

I was to be at his birthday party that evening at 8:00 pm. I was doing

fine at my going away party and explained why I had to leave early because

of the future father-in-law birthday thing. Well I'm out in the

parking lot getting in my car to leave and who shows up late but Frank

Jelly, my supervisor. I explain why I've got to go and he tells me he has

to buy me just one drink. OK, just one!

Having just that

one drink I get into a conversation with an eccentric genius who worked at

Gyrodyne as a designer/machinist and he starts telling me about a replica

Fokker D-VII that he's building in his barn. To this day I can't remember

his name, The only thing I remember after that was 3 hrs. later when I got

home at my parents house feeling no pain the door-bell rang, my mom called

me to the door, my mom left and my fiancée with my future father-in-law

sitting in the car proceeded to throw my engagement to her at me. To this

day I can still remember this ring heading straight at me. We were

un-engaged for about 3 weeks and were married the following Sept. Still

married two kids, two grandchildren and many animals later I still

remember those GREAT days in Flower Field working on the

"Sub-liminators"

Sincerely,

Tom Romano, Schenectady, NY |

|

My Gyrodyne

Years

By Lloyd Lilley, Field Services Representative (1963-1969)

I was employed by the Engineering Research Corporation (ERCO) of

Riverdale, MD, working with the naval training devices center in

Jacksonville, Florida. In April of 1963, I happened to notice an

interesting newspaper advertisement by Gyrodyne Company of America, Inc.,

recruiting personnel for the Navy's DASH (Drone Anti-Submarine Helicopter)

program. I made an appointment for an interview at that time and

subsequently met with Art McCarthy, the head of the field-engineering department. I submitted my

resume, completed the interview, and received an offer of employment about

one week later. I reported to Gyrodyne in St. James, New York during the

first week of May 1963. department. I submitted my

resume, completed the interview, and received an offer of employment about

one week later. I reported to Gyrodyne in St. James, New York during the

first week of May 1963.

During the first few days at Gyrodyne, I went through the normal "new

employee" check-in procedures and was thereafter assigned a desk in

the field-engineering department. A formal classroom training programming

was not in existence at the time and it was left up to me to begin

familiarizing myself with the entire program and its components simply

from the available manuals and other materials on hand. I was given a

great deal of help from the field engineering office personnel, and I am

sure my barrage of questions at times would annoy them. They did however

suffer through my learning period without ever showing any displeasure.

It was during this learning period that I began to "earn my

keep" so to speak. Starting with correcting simple typographical

errors in maintenance manuals and progressing to writing manual revisions

as directed by the engineering department, I began writing step-by-step

assembly, disassembly and repair instructions for the electronics

equipment associated with the drone being manufactured by Gyrodyne.

My family was still living in Jacksonville during ties period, leaving me

with a great deal of spare time, both in the evenings and on the weekends.

Having little else to do, I used this free time to enhance my knowledge of

the DASH program and to complete my assigned tasks. Actually, I was

enjoying my work more and more as I learned my way around Gyrodyne. After

a while, I felt so confident that I placed a small sign on the wall beside

my desk that read, “I can do it. Give it to me”. I am afraid I

made a mistake, as I was suddenly inundated with things to do. No matter,

I enjoyed the challenge. The existence of my little sign however, had

spread throughout the building and I must say that I endured more than a

little good-natured kidding for some time.

I had been introduced to Gordon Bolser, a company Vice President,

during my first week at Gyrodyne, and I accidentally ran into him at

dinner one evening. Gordon was aware of the existence of my little sign,

and I am sure he wondered if it had any real significance.

After a

couple of pre-dinner cocktails, be asked me what I was doing at Gyrodyne,

what my goals were, and my overall intent. My immediate reply was, "I

have come here to take your job". The next few moments were a little

scary. I thought I may be fired, but after pausing and having another sip

of his drink, he replied, " Lilley, that's the most marvelous damn

statement I’ve heard in years. Good luck to you".

I suppose

Gordon wanted to "put me in my place" so to speak, and he came

to my desk on Thursday prior to Memorial Day with the following challenge.

As he explained, new employees with fewer than ninety days with Gyrodyne

were not permitted to be absent from work on the day before or the day

after a holiday, except for reasons of illness or company business. In

other words, no personal time off was allowed. Gordon informed me that he

was departing LaGuardia at 3:30 p.m. that afternoon for Jacksonville to

visit his family for the holiday weekend. To test my resourcefulness as he

put it, I was to in some manner, whatever I could come up with, take the

same flight with him to Jacksonville that afternoon and return to Gyrodyne

on Tuesday following Memorial Day without violating company policy.

Further, I was to make the trip at no cost to myself. His last statement

was, "I want to see if that sign of yours means what it says, at

least that "I can do it" part". " I’ll see just now

how damn good you are".

As Gordon

walked away, I knew I would need help with this one. After pondering my

situation for a few minutes, I realized that my only hope was to get others involved. I

took my situation to Art McCarthy and Tom Wilson (field service financial

advisor). For some unknown reason, they immediately assumed Gordon’s

challenge on my behalf. In less than an hour, I not only had reservations

on Gordon’s flight, but I had the seat next to him reserved. It seemed

that there was a ship in port in Mayport, Florida that had recently

completed the FRAM (Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization) program, but

many equipment serial numbers were missing from Gyrodyne’s files. As

prime contractor, it was necessary that Gyrodyne obtain these serial

numbers immediately. That was my assigned mission.

a few minutes, I realized that my only hope was to get others involved. I

took my situation to Art McCarthy and Tom Wilson (field service financial

advisor). For some unknown reason, they immediately assumed Gordon’s

challenge on my behalf. In less than an hour, I not only had reservations

on Gordon’s flight, but I had the seat next to him reserved. It seemed

that there was a ship in port in Mayport, Florida that had recently

completed the FRAM (Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization) program, but

many equipment serial numbers were missing from Gyrodyne’s files. As

prime contractor, it was necessary that Gyrodyne obtain these serial

numbers immediately. That was my assigned mission.

I arrived at

LaGuardia that afternoon, making certain that I kept out of Gordon’s

view. I allowed all passengers to board ahead of me and only at the last

boarding call did I venture aboard the aircraft and take my seat next to

him. As I slid across him to my window seat, I heard him mumble,

"You’re pretty damn good”.

It was

during this period that I had the opportunity to meet Peter J. Papadakos,

principle owner and founder of Gyrodyne Company of America for the first

time. Art McCarthy introduced us at my desk. Peter took note of my little

sign, welcomed me aboard, and congratulated me on the job I had been

doing. We spent a few minutes talking about the progression of the DASH

program and the direction he hoped it would take. He was very encouraging

as he explained some of the upcoming opportunities that might be offered

Gyrodyne. My immediate impressions were of a man forceful, a man

competent, a man focused, and a man dedicated to the successful completion

of the project at hand. Although I had only a few additional face-to-face

meetings with Peter, my views of the man never wavered. He always seemed

very consistent in his demeanor, thereby, I think, lending leadership and

encouragement to all his employees.

I continued

my aforementioned duties in the field service office for the remainder of

the summer months. I was at one point offered a permanent position in the

field service office, but I respectfully declined the offer, as I had had

the opportunity to meet Robert (Bob) Beyer that summer, and it was

suggested that I was designated to replace him in San Diego when be was

transferred to Japan. Warm weather and southern California seemed ideal to

me, and I was particularly pleased when the above suggestion was

confirmed. To that end, I was sent to the Patuxent river flight test

center for a period of about one month before being sent to San Diego

during the first week in October 1963.

There were several

ships in and entering the FRAM (Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization)

program during this period. A great number of mistakes were being made in

the physical layout of the DASH related equipment. In particular, it

seemed, the foul weather restraint system was being miss-installed on

about every ship in the program. It became a costly item, both time and

money wise. To help alleviate this problem, it was decided to visit each

ship in the FRAM program on the west coast on a regular basis in an

attempt to have the DASH equipment installed correctly at the onset. A

great majority of my time in San Diego was spent in visiting shipyards

from Seattle to Long Beach, making certain the designers and builders were

aware of the specific dash requirements.

In May of 1964, I was directed to proceed to the Pearl Harbor Naval

Shipyard to do an initial inspection of the USS RADFORD (DD-446), which

was midway through the FRAM program. We were very fortunate to have

visited this ship at this time. There was very little in the way of DASH

related equipment that had been installed correctly. It required about ten

days of collaboration with the engineering department at the Pearl Harbor

naval shipyard to advise them of and show them the mistakes that had been

made and the corrections required. It was a trip well spent.

Shortly after my

return from Pearl Harbor, it was decided to locate a DASH support team

there. I was fortunate enough to be asked to relocate to Pearl Harbor in

July of 1964. Needless to say, there was no hesitation on my part.

I reported

to Mobile Technical Unit One (MOTU 1) on July 2, 1964. An additional

Gyrodyne representative reported to MOTU 1 about one week later, and

representatives from Babcock Electronics and Boeing about two weeks

thereafter, completing the DASH contingent in Hawaii. MOTU 1 was a part of

COMSERVPAC (Commander Service Forces Pacific Fleet), and consisted of both

military and civilian personnel who provided technical services and

assistance to all naval forces in the mid pacific area. The group

consisted of about twenty military and civilian personnel that formed a

rather close-knit group, both personally and professionally. All were

quite eager to assist each other in any way possible. The DASH program and

the innovative QH-50 drone, being the "new kid on the block",

sparked quite an interest, and required hours of explanation. Many

representatives from other companies took the opportunity to ride various

DASH ships on days when operations were going to be conducted just to view

the uniqueness of the system.

I reported

to Mobile Technical Unit One (MOTU 1) on July 2, 1964. An additional

Gyrodyne representative reported to MOTU 1 about one week later, and

representatives from Babcock Electronics and Boeing about two weeks

thereafter, completing the DASH contingent in Hawaii. MOTU 1 was a part of

COMSERVPAC (Commander Service Forces Pacific Fleet), and consisted of both

military and civilian personnel who provided technical services and

assistance to all naval forces in the mid pacific area. The group

consisted of about twenty military and civilian personnel that formed a

rather close-knit group, both personally and professionally. All were

quite eager to assist each other in any way possible. The DASH program and

the innovative QH-50 drone, being the "new kid on the block",

sparked quite an interest, and required hours of explanation. Many

representatives from other companies took the opportunity to ride various

DASH ships on days when operations were going to be conducted just to view

the uniqueness of the system.

The first

major "happening" in Pearl Harbor was the SQT (ship's

qualification trial) of the USS RADFORD (DD 446) after it finally

completed the FRAM program. Having little else to occupy our time, other

than an occasional transient DASH ship from the west coast, the DASH group

was able to give the USS RADFORD a complete and thorough checkout prior to

the arrival of the SQT team of representatives from the west coast. This

team of representatives, again, consisted of representatives from various

companies involved in the DASH program, and led by a civil service

employee. Their task was to have the USS RADFORD demonstrate their ability

to operate the DASH weapons system to its fullest extent, and upon

successful completion, certify that ship ready to deploy with DASH as a

part of its’ capabilities.

During these

trials, the local DASH team, including myself, was asked to remain ashore,

as it was felt that the SQT team could better perform their duties if only

members of that team were aboard. I could understand the logic of that

request, and I advised the members of my team to honor the aforementioned.

As a result, I was never exactly sure what had occurred when the RADFORD

returned to port on their first day of trials with a severed umbilical

cable, potentially delaying the trials for some time due to other

scheduled post-FRAM trials facing the ship. The ship's captain was

particularly upset with prospects of a possible two-month delay in

completion of the SQT, and he placed a call to MOTU 1 requesting my

presence aboard the ship to discuss the possibilities of repair. Splicing

of the cable was not an option, as the alloy of certain wires in the cable

required silver soldering, an operation that called for temperatures of

around two thousand degrees which would surely damage other parts of the

cable.

After

exhausting all possibilities of repairing the cable, it struck me that

another ship was at the time undergoing FRAM at the Naval Shipyard.

Perhaps the umbilical cable for that ship's DASH installation was on hand.

As good fortune would have it, the cable was found after several hours of

searching in various warehouses with the help of shipyard personnel.

Arrangements were made to borrow this cable and to have it replaced as

soon as possible, and beginning late in the evening, I removed the old

cable from the associated junction box and replaced it with the new one.

It was a long night, but by reveille, the cable had been replaced,

thoroughly checked out, and was declared ready to be used. Much to the

amazement of the SQT team, the ship was ready to resume trials by 9:00

a.m. Trials did resume that

day and came to a successful completion on schedule. At the Captain's

insistence however, I was to be aboard the ship for the remainder of the

trials. It all worked out to everyone's satisfaction.

It was a long night, but by reveille, the cable had been replaced,

thoroughly checked out, and was declared ready to be used. Much to the

amazement of the SQT team, the ship was ready to resume trials by 9:00

a.m. Trials did resume that

day and came to a successful completion on schedule. At the Captain's

insistence however, I was to be aboard the ship for the remainder of the

trials. It all worked out to everyone's satisfaction.

The RADFORD began

to log considerable flight time. The Captain had become quite a DASH

proponent and he insisted that the ship become proficient in the use of

the system. Whenever possible they operated with submarines in the area,

engaging them in mock ASW operations. At other times they simply flew,

coordinating the operations of the tracking radar, the combat information

center (CIC) and the ship's sonar. Having been issued a standing

invitation by the Captain to come aboard and participate in any of the

ship's operations, I was present during most of the time that they were

engaged in the aforementioned operations, and it was during one of these

operations that I mentioned to the Captain the existence of an airborne

detection device known as M.A.D. (magnetic anomaly detection).

I was

familiar with the equipment, having operated it during my own tenure in

the Navy as a member of a blimp squadron flight crew. We together surmised

how great it would be to have this equipment aboard the QH-50 drone, and

to utilize that combination to sweep areas ahead of convoys for instance,

and to further utilize the combination to localize and to pinpoint

submarine contacts. But, alas, there was no process known to either of us

that would allow the results of a MAD contact to be transmitted from the

QH-50 to the ship's combat information center. We did visualize however,

the possibilities of long-range submarine detection utilizing the QH-50 as

a detection platform. As we continued to consider the possibilities, my

thoughts returned to my own days in the Navy, and I recalled using a

passive Sonobuoy System for listening to underwater sounds made by a

submarine.

As seen at right, by dropping channelized Sonobouys in a known array, one could track

a submarine simply by

comparing the sound levels at the various Sonobouys. In other words, the

submarine was closest to the Sonobuoy that presented the highest audio

level. As archaic as it was at the time, I felt that it might be of

considerable value to a ship whose sonar was able to detect underwater

objects only a few thousand yards away. I also knew that this old passive

system had been long since replaced by a far more accurate and

sophisticated system known as “JEZEBEL”. It came to mind that we might

be able to obtain some of the older Sonobouys along with the associated

receiving equipment, for a simple “give it a try” project. Captain

Wettlaufer of the USS RADFORD

and I traveled to the Naval Air Station, Barbers Point, Hawaii, to

investigate the possibility of obtaining the aforementioned equipment.

Upon arriving at Barbers Point, we accidentally ran into a Navy pilot

(Commander "Red" Clayton) with whom I had flown during my years

in the Navy. After explaining our mission, Commander Clayton, being quite

familiar with the system we were attempting to obtain, became quite

instrumental in resolving our problem. He immediately led us to a storage

area where we found a “cache” of both SSQ-2 Sonobouys and the

associated receiving equipment. He even assisted us in making arrangements

to “borrow” some of this equipment, and we left Barbers Point with

everything we needed to make some initial tests.

As seen at right, by dropping channelized Sonobouys in a known array, one could track

a submarine simply by

comparing the sound levels at the various Sonobouys. In other words, the

submarine was closest to the Sonobuoy that presented the highest audio

level. As archaic as it was at the time, I felt that it might be of

considerable value to a ship whose sonar was able to detect underwater

objects only a few thousand yards away. I also knew that this old passive

system had been long since replaced by a far more accurate and

sophisticated system known as “JEZEBEL”. It came to mind that we might

be able to obtain some of the older Sonobouys along with the associated

receiving equipment, for a simple “give it a try” project. Captain

Wettlaufer of the USS RADFORD

and I traveled to the Naval Air Station, Barbers Point, Hawaii, to

investigate the possibility of obtaining the aforementioned equipment.

Upon arriving at Barbers Point, we accidentally ran into a Navy pilot

(Commander "Red" Clayton) with whom I had flown during my years

in the Navy. After explaining our mission, Commander Clayton, being quite

familiar with the system we were attempting to obtain, became quite

instrumental in resolving our problem. He immediately led us to a storage

area where we found a “cache” of both SSQ-2 Sonobouys and the

associated receiving equipment. He even assisted us in making arrangements

to “borrow” some of this equipment, and we left Barbers Point with

everything we needed to make some initial tests.

I first

took the equipment to the MOTU 1 electronics shop, as it needed to be

modified somewhat to operate aboard ship (it needed a different power

supply). After crossing this minor hurdle, I modified the Sonobuoy to

operate on shop power, released the underwater transducer, and we had a

transmitting and receiving device that became quite a novelty at MOTU 1.

My next step was to install the receiving equipment aboard the

RADFORD. The antenna for the equipment needed to be installed as high on

the mast as possible, and Captain Wettlaufer gladly supplied personnel to

assist

me in the installation of the antenna and the associated coaxial

cable to the receiving equipment, which we mounted in a "cubby

hole" amidships on the main deck. With the receiving equipment in

place, I again checked the reception by operating the Sonobuoy from shore

power (connected to my car's battery), while driving around the naval

base. Again, our system seemed to be doing as we expected. We were now

looking forward to our first trial at sea. me in the installation of the antenna and the associated coaxial

cable to the receiving equipment, which we mounted in a "cubby

hole" amidships on the main deck. With the receiving equipment in

place, I again checked the reception by operating the Sonobuoy from shore

power (connected to my car's battery), while driving around the naval

base. Again, our system seemed to be doing as we expected. We were now

looking forward to our first trial at sea.

The first

actual trial of our new found system was accomplished by simply dumping a

Sonobuoy over the side, waiting for it to activate (this took a few

minutes), and then listening to the sounds our own ship made as we

increased and decreased the distances between the ship and the Sonobuoy.

Needless to say, a great number of shipboard personnel used the headphones

to listen within the next couple of hours. We did back away from the

Sonobuoy at one point for a distance of about three miles while an

accompanying vessel made a close pass on our Sonobuoy. This too went quite

well and we returned to port with a great deal more enthusiasm than

before.

Our next

step was to devise a means of delivering Sonobouys via the QH-50. With a

small and almost insignificant modification to an existing bomb rack, I

devised a means of mounting and delivering four Sonobouys anywhere within

range. This did however reduce the torpedo load to one torpedo rather than

two.

At this

juncture, the RADFORD was about to deploy to the Far East for a period of

six months. Higher naval authorities in the mid pacific area had expressed

considerable interest in the Sonobuoy delivery system and its

possibilities, and I was directed to accompany the RADFORD to Subic Bay in

the Philippines and to continue our testing during the transit. The

decision to send me with the RADFORD was finalized only two hours prior to

departure, and I was unable to make the departure time. However, I boarded

a MATS (Military Air Transportation System) flight the next morning and the RADFORD picked me up at Midway Island the next day. Two other ships

and one submarine, all out of Pearl Harbor, accompanied us and it was our

intent to practice our delivery and detection techniques for the next few

days. However, Mother Nature intervened in the form of a very violent

three-day storm, forcing us to curtail all operations. The storm was so

violent that one ship in our company sustained a cracked hull,

contaminating its fuel tanks, and eventually requiring that it be towed

into Guam. Considerable underway repairs to the RADFORD were required

after leaving Guam, and this fact prevented us from performing any of our

planned tests with the DASH system. I was able to assist the RADFORD in

several repairs in other areas however, and to this extent, it was not a

totally wasted trip. I departed the RADFORD in Subic Bay and made my way

back to Pearl Harbor.

the RADFORD picked me up at Midway Island the next day. Two other ships

and one submarine, all out of Pearl Harbor, accompanied us and it was our

intent to practice our delivery and detection techniques for the next few

days. However, Mother Nature intervened in the form of a very violent

three-day storm, forcing us to curtail all operations. The storm was so

violent that one ship in our company sustained a cracked hull,

contaminating its fuel tanks, and eventually requiring that it be towed

into Guam. Considerable underway repairs to the RADFORD were required

after leaving Guam, and this fact prevented us from performing any of our

planned tests with the DASH system. I was able to assist the RADFORD in

several repairs in other areas however, and to this extent, it was not a

totally wasted trip. I departed the RADFORD in Subic Bay and made my way

back to Pearl Harbor.

I spent the

next few months assisting the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard with the FRAM

program, and readying newly FRAM’d ships for their SQTs, in addition to

providing assistance to transient west coast ships deploying with DASH

aboard. It was during this period that I began to consider the possibility

and feasibility of integrating the true airborne “JEZEBEL” system into

the DASH program. Upon the RADFORD’s return from deployment, I presented

my ideas to Captain Wettlaufer, and he again actively pursued the

possibilities. My limited knowledge of the true “JEZEBEL” system and

its full capabilities dictated that we enlist the aid of naval air

personnel to answer some of our questions. With new plans and a great deal

of enthusiasm, we approached a ranking Admiral at Pearl Harbor, where

Captain Wettlaufer expressed our desire to create our own “Destroyer

Jezebel”, or “DESJEZ” system. This Admiral was already familiar with

the work we had done with the SSQ-2 Sonobouys, and he himself became a

proponent for the development of a true “Destroyer Jezebel” system. I

do recall his being somewhat bewildered at the fact that the surface navy

had never been offered, or never even knew of a system called

“JEZEBEL” with its seemingly advanced capabilities, and it honed his

interest even more. His many inquiries and requests, some reaching as far

as Washington, for true “JEZEBEL” equipment for testing aboard the USS

RADFORD, were all met with one simple explanation: “unavailable”.

After exhausting all avenues of procurement, sadly to say, the attempt to

further develop the "DESJEZ" system in Hawaii was terminated.

It was noted

that we were perhaps “too far from Washington to be involved in such

development activities”. I had been directed from the onset to provide a

weekly progress report to the field service office of Gyrodyne concerning

activities related to the development of the DESJEZ system. I did provide

this information via the officer- in-charge of MOTU 1, and I am sure the

field service office received it. Apparently, Gyrodyne was unable to gain

further support for the development of “DESJEZ”, as I am sure they

must have tried. I did receive considerable “moral” support from that

end.

After the

demise of “DESJEZ” in Hawaii, I did have the opportunity to explore at

least one other alternate use of the DASH weapon system. I was approached

by a fellow MOTU 1 Western Electric Representative whose area of expertise

was the fire control and QH-50 tracking radar. This representative had

discovered several older and presently unused airdropped radar beacon

transmitting devices, stored in a warehouse aboard a marine base in

Kaneohe, Hawaii. It seemed that the Western Electric Representative was

the only person around who knew anything about the use of the device,

which, when dropped from an aircraft, simply opened and up righted itself

and began transmitting a radar beacon signal that could be detected by the

fire control radar aboard ship, knowing the exact location of and distance

to the radar beacon, would allow the fire control radar to offset the

ship's guns and fire them with deadly accuracy. Once the beacon was

dropped and activated, its capabilities were available to any ship. Our

intent was to devise a means of dropping the beacon from the QH-50 drone,

and to this end, we were invited to demonstrate the use of the beacon at

the firing range on the island of Kahoolawe. The beacon was manually

placed and activated for these trials, and the first attempt to use it

proved to be far more successful than anyone had imagined.

We were then

directed to continue immediately with devising a means of delivering the

beacon via the QH-50, but when Navy officials requested more of the

beacons for our program it was discovered that they had all been

transferred for use in the Far East. No more beacons were available to us.

Thus, again, efforts to develop additional roles for the QH-50 were

thwarted. No further developments in this area were pursued.

The Vietnam

conflict had grown considerably, and the next several months were spent

assisting a great number of DASH equipped ships in transit to and from the

Far East. In order to make myself more available to these transient ships,

I was transferred from MOTO 1 directly to the offices of Destroyer

Flotilla Five at the Pearl Harbor Naval Station. DESFLT Five felt they

could more effectively utilize my services if I were assigned directly to

their office.

I was subsequently recalled to Gyrodyne, St. James, New York to

discuss the development work I had done with "DESJEZ", and to

attend an introductory seminar in the Boston area concerning “SNOOPY”

(reconnaissance variant of the QH-50 equipped with real-time TV cameras).

A number of “SNOOPY” equipped ships from the west coast had begun to

deploy to the Far East with the system on board, and it was necessary that

I gain some expertise in this new area. This was a fortunate occurrence,

as I was shortly thereafter directed to Japan and subsequently to Subic

Bay in the Philippines to board the USS CHEVALIER (DD-805), a “SNOOPY” equipped

ship headed for the Vietnam area for a period of approximately ten days of

trials with “SNOOPY”. Those ten days was extended to thirty-two days,

and we had the opportunity to gain some notable successes with the system.

Our target location, gunfire spotting, and immediate battle damage

assessment were greatly enhanced by the “SNOOPY” system. On at least

one occasion we were able to locate, identify, and direct Air Force

aircraft to targets with amazing results. We experienced no major problems

with the “SNOOPY” equipment or trials. Nearing the end of our stay in the area, however, we did

experience the loss of one QH-50, due apparently to enemy gunfire. We

retrieved another of our aircraft that had sustained in-flight damage from

enemy gunfire, damage in the form of several bullet holes in the rotors.

Our trials had ended successfully however, and we were relieved on station

by another “SNOOPY” equipped ship on the day following. I departed the

USS CHEVALIER in Taiwan a few days later and returned to Japan for a

debriefing conference, and eventually to my normal duties in Pearl Harbor.

Although I had spent some time in the Navy myself, I realized that I had

never gotten aboard a ship, nor had I ever gotten into a shooting war

until I became a civilian. I felt it to be a little ironic. occurrence,

as I was shortly thereafter directed to Japan and subsequently to Subic

Bay in the Philippines to board the USS CHEVALIER (DD-805), a “SNOOPY” equipped

ship headed for the Vietnam area for a period of approximately ten days of

trials with “SNOOPY”. Those ten days was extended to thirty-two days,

and we had the opportunity to gain some notable successes with the system.

Our target location, gunfire spotting, and immediate battle damage

assessment were greatly enhanced by the “SNOOPY” system. On at least

one occasion we were able to locate, identify, and direct Air Force

aircraft to targets with amazing results. We experienced no major problems

with the “SNOOPY” equipment or trials. Nearing the end of our stay in the area, however, we did

experience the loss of one QH-50, due apparently to enemy gunfire. We

retrieved another of our aircraft that had sustained in-flight damage from

enemy gunfire, damage in the form of several bullet holes in the rotors.

Our trials had ended successfully however, and we were relieved on station

by another “SNOOPY” equipped ship on the day following. I departed the

USS CHEVALIER in Taiwan a few days later and returned to Japan for a

debriefing conference, and eventually to my normal duties in Pearl Harbor.

Although I had spent some time in the Navy myself, I realized that I had

never gotten aboard a ship, nor had I ever gotten into a shooting war

until I became a civilian. I felt it to be a little ironic.

During the

early months of 1968, I began to note with some apprehension, that many of

the DASH support billets were being canceled, funding for the DASH program

was being reduced, and what appeared to me to be an overall lack of

support for further development or enhancement of the DASH Weapons System

having lived in Hawaii now for almost four years, which was a marvelous

experience for my family and myself, I felt a personal need to return to

the mainstream of things. I knew that I would need to make personal plans

for the future, depending upon the direction the DASH program turned. To

this end, I asked for and received a transfer to the Mayport Florida Naval

Station. I reported to a support unit there in the summer of 1968.

Many of the

DASH-equipped destroyers from the east coast had been deployed to the Far

East during this period, and the next year was quite uneventful. I can

recall being sent to Puerto Rico for a period of one month to support DASH

operations during a large ASW training exercise. The exercise was delayed

for a period of two weeks after my arrival there, and eventually canceled

altogether. Nothing of any significance that I can recall occurred during

the remainder of my stay in Mayport.

Billets for

Gyrodyne personnel continued to be canceled. Many former Gyrodyne

personnel had gained employment as federal civil service employees in

support of the DASH program, and many other Gyrodyne employees had simply

left the organization. I felt sure the “beginning of the end” was at

hand and began to make alternate personal plans for the future. It was at

this time that I was suddenly asked to transfer from Mayport to Quonset

Point, Rhode Island. I was somewhat surprised and bewildered by this turn

of events, but I complied with the company’s request and reported to

Quonset Point at the designated time.

Much, much

to my surprise did I find upon my arrival there, a full and complete set

of true “JEZEBEL” equipment, the same equipment we had tried so hard

to obtain for installation aboard the USS RADFORD during my time in

Hawaii. This equipment had somehow suddenly and mysteriously become

available for installation aboard a DASH equipped ship, at Quonset point,

and I was “directed” by a fellow Gyrodyne employee to begin the

installation on the very next day. Needless to say, and perhaps

overreacting to these events, I became quite upset, upset to the point

that it prompted me to immediately return to St. James and submit my

resignation, thus ending my career with Gyrodyne Company of America. Much, much

to my surprise did I find upon my arrival there, a full and complete set

of true “JEZEBEL” equipment, the same equipment we had tried so hard

to obtain for installation aboard the USS RADFORD during my time in

Hawaii. This equipment had somehow suddenly and mysteriously become

available for installation aboard a DASH equipped ship, at Quonset point,

and I was “directed” by a fellow Gyrodyne employee to begin the

installation on the very next day. Needless to say, and perhaps

overreacting to these events, I became quite upset, upset to the point

that it prompted me to immediately return to St. James and submit my

resignation, thus ending my career with Gyrodyne Company of America.

I

was on several occasions, following my resignation, contacted by Mr.

Papadakos, inviting me to return to St. James to discuss my decision to

leave Gyrodyne. He was very appreciative of the work I had done while with

his company, and I must admit that there were times when I regretted my

decision to respectfully decline his invitation to return. I had in the

meantime, made other commitments to the furtherance of my own career, and

felt the decision to be in my best interest.

It was

several years later that I learned from one of my own employees, a former

Navy person, that there was indeed a system aboard his ship that was

referred to as “DESJEZ”, and that it utilized Sonobouys to detect and

fingerprint submarines from Navies throughout the world.

I was quite pleased.

My post- Gyrodyne years

1969-present (2002)

After

resigning from Gyrodyne in the fall of 1969, I returned to my hometown of

Bristol, Virginia-Tennessee where I established a general electronics

firm. We were engaged in the design, sales, and installation of

sound/intercom systems for schools, offices, industrial complexes, and

other commercial entities. In addition, we designed and installed cable TV

systems, alarm systems, specialized industrial control systems, and

provided contractual installation and maintenance services on computer

batch terminal equipment for a large North American Corporation. This

business eventually evolved into data processing, computer sales and

service, computer networking, and software support and development.

In 1991, I

suffered a disabling stroke, and was forced to retire but after spending

about eighteen months in both supervised and unsupervised rehabilitation

learning to walk and to perform other menial physical tasks, I regained

about ninety percent of my former physical abilities. My golf handicap

soared from two up to a six, but under the circumstances, I am very

comfortable with that.

After regaining

much of my former physical ability, I began to assist one of my former

customers, a fairly large and locally based pizza firm, with their

continued efforts to “computerize” their entire business. I have

continued to provide them with consulting services over the past nine

years in the areas of program development, hardware procurement,

installation, communications, and maintenance. The nature of my assistance

to this organization over this period has provided ample time for travel,

boating, fishing, golfing, and many other leisure activities.

Under the aforementioned circumstances, I found it somewhat difficult to

totally and entirely cease all work related activities until just one

month ago, shortly past my seventieth birthday, when I totally retired. My

near term plans include an initial short cruise in the boat along the

intracoastal waterway of North Carolina, with thoughts toward extending

that venture perhaps to areas much farther south. My wife, Patricia and I

physically reside still in our hometown of Bristol, Tennessee, but I

believe our hearts and minds will always remain in Hawaii. There is a

possibility that we will return for the third time since 1968 to celebrate

our fiftieth wedding anniversary this year.

|

|

My Time as Buyer and Major Subcontract

Administrator

By Ed Delp, (1960 to 1965 )

We

were all preparing for series of negotiations to make the necessary awards

for the contract and the Cost Analyst assigned to me (Joe, don’t remember

his last name) and I were assigned to go to Motorola and then Babcock as the

first team out because Mr. Peter J. Papadakos (President of Gyrodyne) Dad

didn’t think anyone could be successful negotiating with either of them. The

next negotiations were to be at Lear Siegler in Santa Monica. We

were all preparing for series of negotiations to make the necessary awards

for the contract and the Cost Analyst assigned to me (Joe, don’t remember

his last name) and I were assigned to go to Motorola and then Babcock as the

first team out because Mr. Peter J. Papadakos (President of Gyrodyne) Dad

didn’t think anyone could be successful negotiating with either of them. The

next negotiations were to be at Lear Siegler in Santa Monica.

The Program Manager at Motorola, Bob Blackert, had been

told on previous occasions that only PJP could approve purchases. I had

Motorola at a point where a bid in the $4000 plus range was now in the $3000

plus range, each for 300 plus units, and I structured a memorandum of

agreement which Motorola agreed to but Bob said that he needed to have

Peter’s approval that day or the agreement was off the table. It was already

late in Phoenix, but Bob had a number that was good to reach Peter when

there was something important to talk about. He got Peter on the phone and

explained where we were followed by the agreed to price followed by

questioning who could sign the agreement, a couple of “yes Peter”’s

and an “Ed, Peter wants to talk to you”. I got on the line and he said, in a

very happy way, “Sign the f_____g thing yourself”.

He then asked me where I was going next and I told him

Babcock to which he said to call him when we were finished. I had a similar

experience at Babcock at a lower price level (around $2000 down to just

under $1000 as I remember) and when I talked to him he said he knew that

Lear Siegler wasn’t my supplier but asked if I would I join the negotiating

team. The reason I even bring this part up is something about your father

that not enough people knew or understood. The month was December and I told

him that my wife was pregnant and due in the not too distant future. His

response was to tell me that my wife was much more important and I should

come home. My son was born on January 22nd. I already had a great respect

for Mr. Papadakos as a business man, I then acquired a great respect for him

as a human being. Gyrodyne still stands as the number one experience in my

career followed years later by my 13 years at Northrop which never would

have happened without Mr. Papadakos and Gyrodyne.

Hope I haven’t bored you with this, it will never be boring

to me.

Ed Delp

April 3, 2011

P.S. – I was over in the Quality building looking at a dead moth that the

inspector found inside of a decoder, trying to figure out how we could have

a little fun with it (avionics bug). They always had music playing on a

radio, loud enough for everyone to hear the music, when a news flash came on

announcing that President Kennedy had just been shot. Funny, some of the

things you never forget.

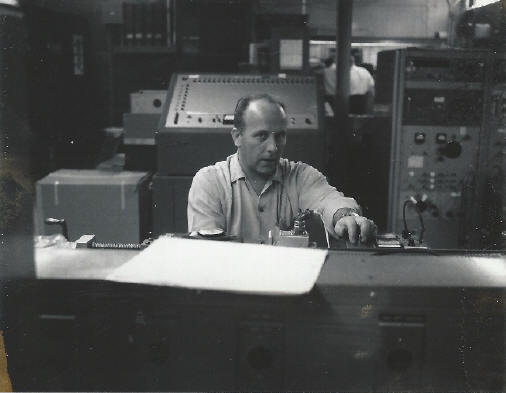

Finally, I love the Gyrodyne Foundation; they bring back

lots of good memories. The original flotation gear pressure cylinder was

made by a company in LA and there was a very senior citizen who was the only

one that seemed to be able to weld the two halves with any repeatable

success. Of course, the decoder and receiver (shown right) (Motorola and

Babcock) were two of my babies

|

|

Remembering the

Machine Shop

By George M. Kowalchuk, Machinist (1962 - 1972)

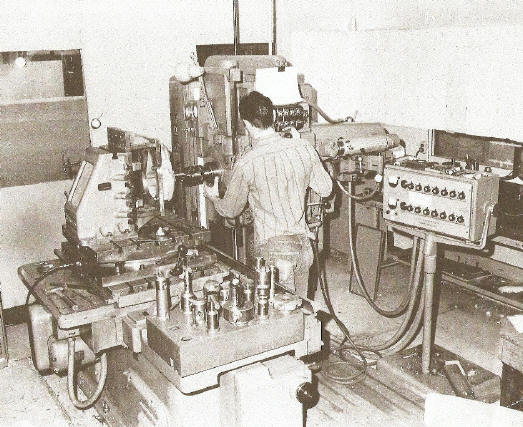

The accompanying photograph of me was taken on January 28th, 1970 in

Gyrodyne's climate controlled jig boring / jig milling room attached to

its general machining facility. In this area, the final steps of the

manufacturing process were completed on all parts requiring very close

tolerance finish machining (pitch horns, bell and transmission housings,

etc.) along with experimental projects and model crafting. The machine

pictured is a DeVlieg Spiramatic Jig Mill in process of cutting a

retaining ring groove in a transfer housing.

The accompanying photograph of me was taken on January 28th, 1970 in

Gyrodyne's climate controlled jig boring / jig milling room attached to

its general machining facility. In this area, the final steps of the

manufacturing process were completed on all parts requiring very close

tolerance finish machining (pitch horns, bell and transmission housings,

etc.) along with experimental projects and model crafting. The machine

pictured is a DeVlieg Spiramatic Jig Mill in process of cutting a

retaining ring groove in a transfer housing.

At one

of the Company's periodic meetings, I believe it was in 1969, Mr.

Papadakos (the President of Gyrodyne) presented a film to employees of

scenes taken by a camera aboard a modified drone during a photo

reconnaissance mission in Vietnam. As he narrated the film and described

its content in detail, I realized that this drone was carrying the

prototype camera / machine gun mount I had finished machining a few weeks

before. I recall noticing the design engineer, drawings spread over every

available flat surface, anxiously giving them a last minute review. I was

also quite nervous since this mount was to be on its way to Viet Nam that

very night. It went on its way without a hitch and not long after, two

helicopters were made completing the Qh-50 production (Aug. 29, 1969).

Much of the work on the Heavy Lift Helicopter Model (HLH competition) was

done on Moore Vertical Jig Boring Machines.......This model was quite

detailed with functioning parts (blades, winch assembly, and sky crane

type of framework).......I've often wondered if the model survived the

years.

By 1972 I was one of only five remaining employees and a typical work day

included refurbishing buildings, ground maintenance, occasionally

repairing or manufacturing Drone parts, and lest I forget.....climbing

that scary eighty-foot-high steel ladder to the catwalk atop the now

obsolete drone suspension test rig (T-Rig). The light bulbs in the

aircraft-warning-lights had to be changed periodically and I was the guy

who inherited the job after Andy-The-electrician was laid off.

After a long talk with Mr. Papadakos in which he offered additional job

security restoring "The Cottage" (where Navy representatives and Vendors

met with GCA representatives) to its former glory but no promise of any

increase in salary, I left GCA, along with Harold Jayne, a line technician

who had worked closely for years with Andy Dinkel, Jack Gonzales, and

George Schwears and Bob Chmiel....At that point, ten years had gone by

since my hiring and the work force, that I believe once totaled close to a

thousand, had dwindled to three.

I

passed by the Gyrodyne property a while ago and could have sworn I saw

Pete Ackles and the dog.

George M. Kowalchuk

(Sent by U.S. Mail - Posted March 16, 2011)

|

|

|

Remembering Don Anderson, Electrician

(1964-1972)

By Alan Anderson

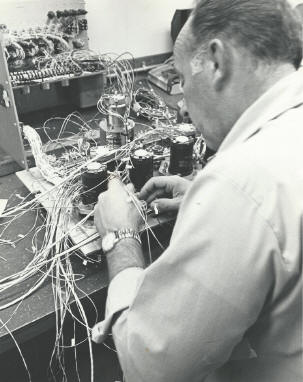

My

Father, Don worked in the electrical shop at Gyrodyne Company of

America, providing support to the assembly line in Bldg 7, and also the

flight test cells at the Air Strip and at Bldg 18 (Helipad). My

Father, Don worked in the electrical shop at Gyrodyne Company of

America, providing support to the assembly line in Bldg 7, and also the

flight test cells at the Air Strip and at Bldg 18 (Helipad).

Don fabricated and installed wiring harnesses,

instrumentation consoles (per photo), command and control equipment for

the QH-50 Drones. He was dispatched a few times to support on-ship

installations aboard Navy Destroyers anchored in the Long Island Sound

awaiting the upgrades.

In the

summer of 1971 Don was assigned to support flight tests out at Indian

Springs (now Creech AFB)/ Mercury, Nevada. The Anderson and George

Schwears families both traveled to Las Vegas. Don and George supported

with flight test activities during that entire summer. Don was employed

at Gyrodyne from 1964 to 1972 and endured the big lay-off when QH-50

Production ended in 1969. He staying on until only a few employees where

left. He assisted with lawn and grounds maintenance along with general

facility maintenance. Don had the high catwalk detail on the T-Rig

Cells, climbing the towers to change out the warning lights. Upon be

laid off that high wire act was passed onto George Kowalchuk as noted in

his story of "Andy the electrician". In the

summer of 1971 Don was assigned to support flight tests out at Indian

Springs (now Creech AFB)/ Mercury, Nevada. The Anderson and George

Schwears families both traveled to Las Vegas. Don and George supported

with flight test activities during that entire summer. Don was employed

at Gyrodyne from 1964 to 1972 and endured the big lay-off when QH-50

Production ended in 1969. He staying on until only a few employees where

left. He assisted with lawn and grounds maintenance along with general

facility maintenance. Don had the high catwalk detail on the T-Rig

Cells, climbing the towers to change out the warning lights. Upon be

laid off that high wire act was passed onto George Kowalchuk as noted in

his story of "Andy the electrician".

After the layoff the family decision was made to head

west, moving from home in Lake Ronkonkoma in the early summer of '72.

Arriving in Phoenix, and finding that work for out of staters was

impossible to get during those years. Pushing on to California he worked

at Datron Systems Inc. in Northridge Ca.

After a few years he hired on with Northrop in 1975. Don was a

instrumentation electrician, wiring up cockpit systems and harnesses,

supporting a number of aircraft on the production lines and check out

areas. Through the years, supporting various aircraft programs, T38, F5,

F20 Tiger Shark, F18, F23 prototype and finally retired in 1987 while on

the B-2 Bomber project located at the southbase flight test complex at

Edwards AFB Ca.

After residing in Lancaster Ca. for a number of years, he moved to

Tehachapi. Enjoying some restful times and his much enjoyed trailering

around the states for a few years RVing. He passed in January 1992. He

would at times reminisce about the QH-50 DASH drone program he helped

with at Gyrodyne, commenting how that project at that time was 30 years

ahead of its time! As a side note before Gyrodyne, he also worked

at Arma Corporation and also Republic Aviation.

As a lad he raced stock cars at Dexter Park, Queens and Freeport

Stadiums. Fun times for a young lad from Jamaica N.Y.

From the Don Anderson family, Tehachapi Ca.; August 3, 2014

|

|

|

|

|

|

Were working on more! Please be patient! If you are

a former employee, please submit your Gyrodyne "memory" to the

following address (not a hyperlink):

Gyrodyne_History@Yahoo.com

|

|