|

|

|

Born on July 26, 1914 in Portland, Oregon,

Mr. Papadakos' father owned and operated three Greek restaurants. In the year

1919, the family moved to Norfolk Virginia where Mr. Papadakos' father also

again operated several Greek restaurants. Unfortunately, at

age seven in May of 1921, Mr. Papadakos' father was asked to return to Greece to take over the

family farm business in the small village of Potamia. Leaving America, although at a young age, was a traumatic

event for the young man, for the home his two siblings and parents soon occupied was a one room, dirt floored cabin that sat on a 40 acre olive tree

farm. Having come from a multi-room home with indoor plumbing in Norfolk

Virginia caused

the then young Mr. Papadakos to vow to return to America and leave the solitary mountains of

Potamia and later Sparta in 1932. For the next 10 years, the young man learned what hard farm work was

all about and hardened his resolve to return to America. At age 10, however, he

was involved in a cart accident which resulted in a broken left leg. Greek

medicine being what it was at that time, the injury soon became infected causing

osteomyelitis (inflammation of bone or bone marrow,

caused by infection by microorganisms) and he almost lost his life.

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

While the Model 2B was being flown for the

1949 Air Force demonstration,

Mr. Papadakos' brother, Nicholas, was running an office out of 80 Wall Street, Manhattan, New

York, selling common stock to anyone who would listen to their sales pitch. In

fact, the Model 2B was being used more and more as a sales tool- on any given

weekend, the 2B would be used to give demonstration rides for potential stock

purchasers. This hard work paid off, when on July 1, 1951, Gyrodyne acquired a tract of

land at St. James, Long Island, New York.

1949 Air Force demonstration,

Mr. Papadakos' brother, Nicholas, was running an office out of 80 Wall Street, Manhattan, New

York, selling common stock to anyone who would listen to their sales pitch. In

fact, the Model 2B was being used more and more as a sales tool- on any given

weekend, the 2B would be used to give demonstration rides for potential stock

purchasers. This hard work paid off, when on July 1, 1951, Gyrodyne acquired a tract of

land at St. James, Long Island, New York.

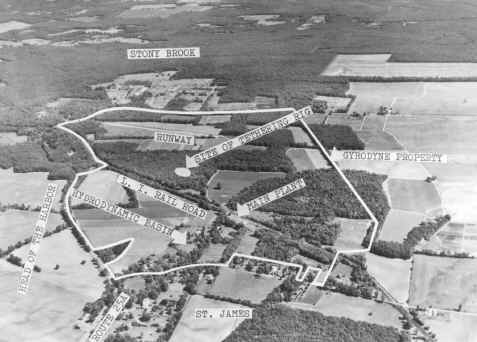

Originally called

"Flowerfield" (map at right), the property had been a flower nursery,

run by a retired General Motors executive's wife. The GM executive had acquired

the original 1000 acres as part of a retirement package from GM. Mr. Papadakos

acquired a 500 acre tract for Gyrodyne from them, but did not see the usefulness of about

180 acres that were on the other side of a country road. He

later

decided to donate the property to the State of New York, which wanted to build a

University on the site. Then Governor Rockefeller (seen left with Mr.

Papadakos on July 17, 1962), made Mr. Papadakos a Honorary Trustee for Life and

Member of the Council,

for the State University at Stony Brook for his generous donation, on June 9,

1966.

later

decided to donate the property to the State of New York, which wanted to build a

University on the site. Then Governor Rockefeller (seen left with Mr.

Papadakos on July 17, 1962), made Mr. Papadakos a Honorary Trustee for Life and

Member of the Council,

for the State University at Stony Brook for his generous donation, on June 9,

1966.

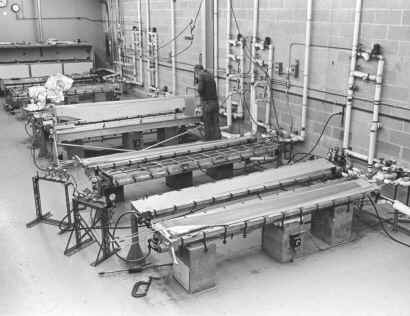

On the 320 acres that remained, several buildings and two homes existed on the property. The bulb storage facility, now called Bldg 1) totaled some 28,000 sq.ft. which was transformed into executive offices, engineering, drafting and machine shop facilities. In June 1951, Gyrodyne moved to this new location which provided the Company with both a permanent home and a base for future expansion. From this new base of operations, the young Gyrodyne company began to perform subcontract work for Long Island's strong defense base.

Such companies as Republic and Grumman were customers for Gyrodyne's machine

shop (seen left) and allowed for new tools

and machines to be acquired and underwrite the expenses associated with

the helicopter development. When business slowed, there still was the surplus

Peonies flower bulbs left over from the Flowerfield days that could be

sold. Most of the 50

or so part-time employees (most had other jobs) working for this small start-up

were paid in Gyrodyne stock. A machinist made $ 5.00 per hour and that

translated in 1 share of common stock per hour. Mr. Papadakos felt that making

his employees shareholders of the firm was his best chance of holding onto his

quality machinists and engineers which were in high demand at the time.

sold. Most of the 50

or so part-time employees (most had other jobs) working for this small start-up

were paid in Gyrodyne stock. A machinist made $ 5.00 per hour and that

translated in 1 share of common stock per hour. Mr. Papadakos felt that making

his employees shareholders of the firm was his best chance of holding onto his

quality machinists and engineers which were in high demand at the time.

In 1951, Mr. Papadakos sought a better way to control the model 2B. He knew he had to modify the airframe, but did not want to take his only flying aircraft apart. One evening, a group of engineers gathered at the company's new facilities at Flowerfield. The engineers saw what they needed to do- they literally cut the Model 2B in half in order to widen it and also lengthen the cabin; all without Mr. Papadakos' knowledge. Needless to say, many stressful days soon followed!

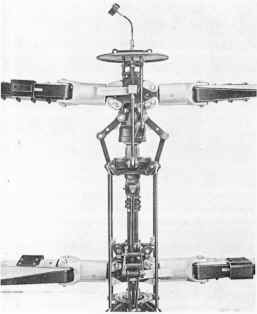

His Gyrodyne crew soon modified the

model 2B by also

removing the two side engines (as seen right).

Also added were movable tail surfaces, power boost controls and other minor

improvements. In June 1951, Gyrodyne received it's first contract from the Naval

Bureau of Aeronautics. Contract no. NOas 51-1217-f was issued to accumulate and

submit flight test data pertaining to the coaxial configuration. The scope of

the contract was to record the flying qualities of the coaxial configuration.

The tests were to be performed in accordance with the requirements of specified

paragraphs of Specification SR-189.

His Gyrodyne crew soon modified the

model 2B by also

removing the two side engines (as seen right).

Also added were movable tail surfaces, power boost controls and other minor

improvements. In June 1951, Gyrodyne received it's first contract from the Naval

Bureau of Aeronautics. Contract no. NOas 51-1217-f was issued to accumulate and

submit flight test data pertaining to the coaxial configuration. The scope of

the contract was to record the flying qualities of the coaxial configuration.

The tests were to be performed in accordance with the requirements of specified

paragraphs of Specification SR-189.

The now Model 2C was instrumented for the Flight Test Program. The instrumentation package included an oscillograph and a photo panel. The Flight Test Program was completed and final report submitted by December 1952. This was the first documentation of flying qualities of a coaxial rotor helicopter in the United States.

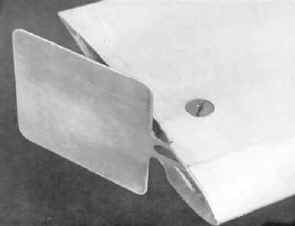

Movable vertical surfaces (rudders) and differential collective in the rotors were incorporated for yaw of the flight test. The results of the instrumented flight test indicated that the coaxial rotor configuration possessed excellent flying qualities in all regimes of flight except for the low speed autorotation where the yaw control means proved inadequate. In order to overcome this difficulty, Gyrodyne continued its research work toward improving the directional control characteristics. In March of 1953, the idea of using tip brakes (seen right) on the tips of the rotor blades was conceived. Flight tests of this concept proved that the problem of effective yaw control in autorotation for a coaxial helicopter had been solved. This was a major breakthrough for the coaxial configuration. The Company applied for and was granted Patent No. 2,835,331.

The Tip brake "made the coaxial possible" Mr. Papadakos was to later

state. If fact, shortly after the development of that tip brake

The Tip brake "made the coaxial possible" Mr. Papadakos was to later

state. If fact, shortly after the development of that tip brake design, the XRON

Rotorcycle contract was awarded and Gyrodyne was on its way to becoming a

major defense contractor when the XRON was droned, thus creating the QH-50A.

As the company's product line was becoming more defined, so were the demands on

Mr. Papadakos that his role change as well. No longer assisting the machinists

with engineering work, Mr. Papadakos was now more of a manager (seen left in

white shirt), making sure that government contracts were achievable and

profitable. By 1963, Gyrodyne had over 700 employees and many stationed all

around the world to support the U.S. Navy's DASH weapon system. However, Mr.

Papadakos, still maintained the position as "head of

marketing" as he

personally would invite dignitaries to his large Gyrodyne establishment and

speak with them of his company's coaxial helicopters and their benefits. When it

appeared that the modified XRON drone would actually become the initial DASH

prototype, major visits by the head Navy personnel increased dramatically by

1961:

design, the XRON

Rotorcycle contract was awarded and Gyrodyne was on its way to becoming a

major defense contractor when the XRON was droned, thus creating the QH-50A.

As the company's product line was becoming more defined, so were the demands on

Mr. Papadakos that his role change as well. No longer assisting the machinists

with engineering work, Mr. Papadakos was now more of a manager (seen left in

white shirt), making sure that government contracts were achievable and

profitable. By 1963, Gyrodyne had over 700 employees and many stationed all

around the world to support the U.S. Navy's DASH weapon system. However, Mr.

Papadakos, still maintained the position as "head of

marketing" as he

personally would invite dignitaries to his large Gyrodyne establishment and

speak with them of his company's coaxial helicopters and their benefits. When it

appeared that the modified XRON drone would actually become the initial DASH

prototype, major visits by the head Navy personnel increased dramatically by

1961:

|

|

|

|

Mr. Papadakos with RADM L.A.Bryan USN; Commander of Destroyer Flotilla Two - July 27, 1961 |

Rear Adm. William H. Groverman (left), Director of Anti-Submarine Research; Gyrodyne's President, Peter J. Papadakos (center) and right is Rear Adm. J.N. Shaffer visiting Gyrodyne's QH-50C DASH manufacturing facility on May 23, 1962. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rear Admiral Speck Visits Gyrodyne's DASH manufacturing facility on May 7, 1963 with QH-50C in the foreground. Mr. Papadakos is behind and left of the QH-50C rotor mast and Admiral Speck is facing him. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mr. Papadakos addressing his employees on June 11, 1964. Every year, Mr. Papadakos would provide a "State of the Business" address so that the employees would understand where the company was heading. |

|

With the development work and subsequent manufacturing of the QH-50A/B, QH-50C and the QH-50D, Mr. Papadakos' life was centered on his evolving company. It seemed that the greatest obstacle to his unmanned machine, that being Naval Aviators, had accepted the idea that manned flight off destroyers was best left to expendable drones, but that was not to last.

While the QH-50C's enemy was that of the undersea "red menace" in the

manner of 300 Soviet fast-attack submarines and was

a weapon system of deterrence, the QH-50D (assembly line at

left) found itself

flying from fewer and fewer destroyers as those DASH equipped ships began to

reach their limit of their operational lifetime. Yet DASH was not being installed on the new

destroyers joining the Navy. While the Navy's ship count was decreasing, the ship's size was

increasing- what had been a "cruiser size vessel" in WW II, was now

"Destroyer size" and the flight deck for those new destroyers was

being made larger and designed around the new LAMPS (Light Airborne

Multi-Mission-Purpose-Ship based) concept helicopters. Suddenly, the Navy had more

QH-50's than it needed and by August 29, 1969 the last Navy QH-50D had been

delivered. Although the Japanese DASH program had begun, it had not taken long

to deliver their twenty D models and parts support for the meticulous Japanese

mechanics was not as strong as it had been for the U.S. Navy. One

Techrep for Gyrodyne had reported that Japanese QH-50s with over 1000 landings,

looked as if they had just come from the assembly line; they were so well

maintained!

While the QH-50C's enemy was that of the undersea "red menace" in the

manner of 300 Soviet fast-attack submarines and was

a weapon system of deterrence, the QH-50D (assembly line at

left) found itself

flying from fewer and fewer destroyers as those DASH equipped ships began to

reach their limit of their operational lifetime. Yet DASH was not being installed on the new

destroyers joining the Navy. While the Navy's ship count was decreasing, the ship's size was

increasing- what had been a "cruiser size vessel" in WW II, was now

"Destroyer size" and the flight deck for those new destroyers was

being made larger and designed around the new LAMPS (Light Airborne

Multi-Mission-Purpose-Ship based) concept helicopters. Suddenly, the Navy had more

QH-50's than it needed and by August 29, 1969 the last Navy QH-50D had been

delivered. Although the Japanese DASH program had begun, it had not taken long

to deliver their twenty D models and parts support for the meticulous Japanese

mechanics was not as strong as it had been for the U.S. Navy. One

Techrep for Gyrodyne had reported that Japanese QH-50s with over 1000 landings,

looked as if they had just come from the assembly line; they were so well

maintained!

Mr. Papadakos had seen this end coming and had positioned the company to

possibly having to survive with little or no government defense work. On June

14, 1966, he formed the Flowerfield Properties wholly-owned subsidiary of the

Gyrodyne Company for the purpose for holding certain assets of the company's

property, investments and its limited partnership in the development of a 3000 acre orange grove in West Palm Beach,

Florida. He also had formed previously, on November 9, 1965, the Gyrodyne

Petroleum wholly-owned subsidiary to hold the assets of the company which had

been invested heavily in oil and gas wells in Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado and

other western states. Further, by 1972 he was remodeling the now empty manufacturing facilities

(seen above-left) and

converting them into small sized suites in order to turn the property into an

industrial park.

Mr. Papadakos had seen this end coming and had positioned the company to

possibly having to survive with little or no government defense work. On June

14, 1966, he formed the Flowerfield Properties wholly-owned subsidiary of the

Gyrodyne Company for the purpose for holding certain assets of the company's

property, investments and its limited partnership in the development of a 3000 acre orange grove in West Palm Beach,

Florida. He also had formed previously, on November 9, 1965, the Gyrodyne

Petroleum wholly-owned subsidiary to hold the assets of the company which had

been invested heavily in oil and gas wells in Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado and

other western states. Further, by 1972 he was remodeling the now empty manufacturing facilities

(seen above-left) and

converting them into small sized suites in order to turn the property into an

industrial park.

During this time, however,

Mr. Papadakos continued to try and convince the U.S. Department of Defense the

value of the coaxial rotor system. In 1969, the Allison powered QH-50E

had flown. In 1970, the two-stage transmission equipped 24' rotor system had

successfully been flown. That aircraft, with a slower rotor RPM of 570, allowed

for greater speed and a payload of close to 2000 lbs! Then in 1971, Mr.

Papadakos used the knowledge gained from the two-stage transmission/24' rotor

system program to enter the Heavy Lift Helicopter (HLH) competition.

Unfortunately, the government decided that after asking for a request for

proposal from all the helicopter companies, to cancel the program. That was the

final request for proposal Gyrodyne ever responded to. Mr. Papadakos felt that

to place his company at risk on the whimsical needs of the military no longer

justified the risks. He placed the remaining helicopters in a part of Gyrodyne's

building no.17 so that what parts support and transmission overhauls required

could occur.

In 1986, Mr. Papadakos was approached by both the Israeli Aircraft Industries

and Dornier Gmbh of Germany to examine the use of the QH-50E

as a modern surveillance drone with modern electronics. While the Israelis

purchased a Technical Data Package containing engineering reports and flight

analysis of the QH-50E, Dornier took their interest much further.

In 1986, Mr. Papadakos was approached by both the Israeli Aircraft Industries

and Dornier Gmbh of Germany to examine the use of the QH-50E

as a modern surveillance drone with modern electronics. While the Israelis

purchased a Technical Data Package containing engineering reports and flight

analysis of the QH-50E, Dornier took their interest much further.

In the Summer of 1986, Dornier sent a three person team to

learn all they could about the QH-50D. After dismantling one aircraft for

inspection and then reassembling it, Dornier flew the aircraft on a hovering

fixture on October 16, 1986. This had been quite an effort for Mr. Papadakos,

who at age 72, found himself working long hours as a Program manager yet again.

Mr. Papadakos also had

found it difficult to find former employees whom after 17

years since the assembly line had shut down, were physically able to do the

work! Luckily, several former employees- like Jack Gonzales, Andrew Dinkel and

George Schwears were available to assist in the effort which concluded when

Dornier asked to take the aircraft back to Germany to integrate their digital

auto-pilot and other modifications

for their then GEAMOS program.

found it difficult to find former employees whom after 17

years since the assembly line had shut down, were physically able to do the

work! Luckily, several former employees- like Jack Gonzales, Andrew Dinkel and

George Schwears were available to assist in the effort which concluded when

Dornier asked to take the aircraft back to Germany to integrate their digital

auto-pilot and other modifications

for their then GEAMOS program.

In the spring of 1987, Mr. Papadakos received visitors from the Navy Air Warfare Center at China Lake-California. The QH-50D was still in use by the Navy as a target to perfect anti-helicopter missiles. The Navy needed rotor blades for those aircraft and requested a bid to have blades made. Mr. Papadakos put a bid on the cost of finding personnel from the production days when Gyrodyne made their own blades (blade shop seen left in 1968). Also, the Navy wanted to take possession of the remaining helicopters they owned under a no-cost contract, but which Gyrodyne had stored for the Navy for safe-keeping. In the fall of 1987, those helicopter assets left with many of the Rotorcycles going to museums and schools which wanted the Porsche engines for shop classes.

From 1988 to 1991 (now 77 years of age), Mr. Papadakos (seen left) spent his

time assisting Dornier with their Drone development. During this time, political

upheaval had changed the mission of the Dornier/QH-50E from that of a land based

drone used for reconnaissance against East Germany to that of being based on a

destroyer to patrol the waters of a unified Germany; like it had been during the

DASH days.

From 1988 to 1991 (now 77 years of age), Mr. Papadakos (seen left) spent his

time assisting Dornier with their Drone development. During this time, political

upheaval had changed the mission of the Dornier/QH-50E from that of a land based

drone used for reconnaissance against East Germany to that of being based on a

destroyer to patrol the waters of a unified Germany; like it had been during the

DASH days.

To see the revitalization and interest of the very aircraft that had launched his company's future some 35 years before was a huge source of pride for not only Mr. Papadakos, but the few still surviving original helicopter employees that had been part of the largest Unmanned Aerial Vehicle program in the world, and it was this source of pride that kept Mr. Papadakos working on advancing his aircraft's role in the world, when he died after a brief illness, at the hospital of a University, which he had donated the land for it to be built on, on May 26, 1992.

Mr. Papadakos' death left many

tasks uncompleted. By 1995, Gyrodyne was producing the 60 plus rotor blades that

the Navy had first asked Mr. Papadakos about in 1987. Total contract value was

over $ 1.4 million.

Mr. Papadakos' death left many

tasks uncompleted. By 1995, Gyrodyne was producing the 60 plus rotor blades that

the Navy had first asked Mr. Papadakos about in 1987. Total contract value was

over $ 1.4 million.

Dornier continued with their program and eventually received

three aircraft and other parts for their Allison engine powered SEAMOS

(seen right) maritime surveillance drone. By 1998, Gyrodyne faced the hard economic realities

of storing helicopter assets that had not generated any income since 1986 in

which the personnel who had created those assets, had simply passed away. Faced

with not being able to service the now only user of the QH-50,

U.S. Army's Program Executive Office, Simulation, Training and

Instrumentation (PEO STRI), Gyrodyne management

made the decision to enter into a Sale Agreement on October 29, 1999 with

Aviodyne U.S.A. of Los Angeles, California to take possession of all remaining

QH-50 assets to support the U.S. military users of the QH-50. Aviodyne also

agreed to support Dornier with any technical questions Dornier could have during

their Drone development. However, after receiving a license payment from

Dornier, the Aviodyne operators closed down on March 20, 2004 and despite

QH-50's still flying for the ARMY, Gyrodyne was no more.

Dornier continued with their program and eventually received

three aircraft and other parts for their Allison engine powered SEAMOS

(seen right) maritime surveillance drone. By 1998, Gyrodyne faced the hard economic realities

of storing helicopter assets that had not generated any income since 1986 in

which the personnel who had created those assets, had simply passed away. Faced

with not being able to service the now only user of the QH-50,

U.S. Army's Program Executive Office, Simulation, Training and

Instrumentation (PEO STRI), Gyrodyne management

made the decision to enter into a Sale Agreement on October 29, 1999 with

Aviodyne U.S.A. of Los Angeles, California to take possession of all remaining

QH-50 assets to support the U.S. military users of the QH-50. Aviodyne also

agreed to support Dornier with any technical questions Dornier could have during

their Drone development. However, after receiving a license payment from

Dornier, the Aviodyne operators closed down on March 20, 2004 and despite

QH-50's still flying for the ARMY, Gyrodyne was no more.

By May 2006, the QH-50 had flown its final flight

and a select few were restored and placed in National museums by this Foundation

so that the legacy of Mr. Papadakos, his employees and those servicemen who flew

the QH-50s during their military service could be seen.

![]()

![]()

|

The name "Gyrodyne" in its stylized

form above, is the Trademark of and owned by the Gyrodyne Helicopter Historical

Foundation; unauthorized use is PROHIBITED by Federal Law. All Photographs, technical specifications, and

content are herein copyrighted and owned exclusively by Gyrodyne Helicopter

Historical Foundation, unless otherwise stated. All Rights Reserved

©2013. |